It could be considered self indulgent to devote a whole one of these blogs to clothing. In our industrial culture- clothes have become so easy to obtain that they seem to have faded in significance compared to food (a lot of it is still grown in this country), housing (there’s a shortage and it's too expensive) or energy (we’re beholden to corporations . Clothes often seem to sit under the subheading feminine indulgence, (entirely deliberate propaganda for many reasons), But perhaps a brief thought experiment into what life would be like without clothes, brings their importance back to our attention!

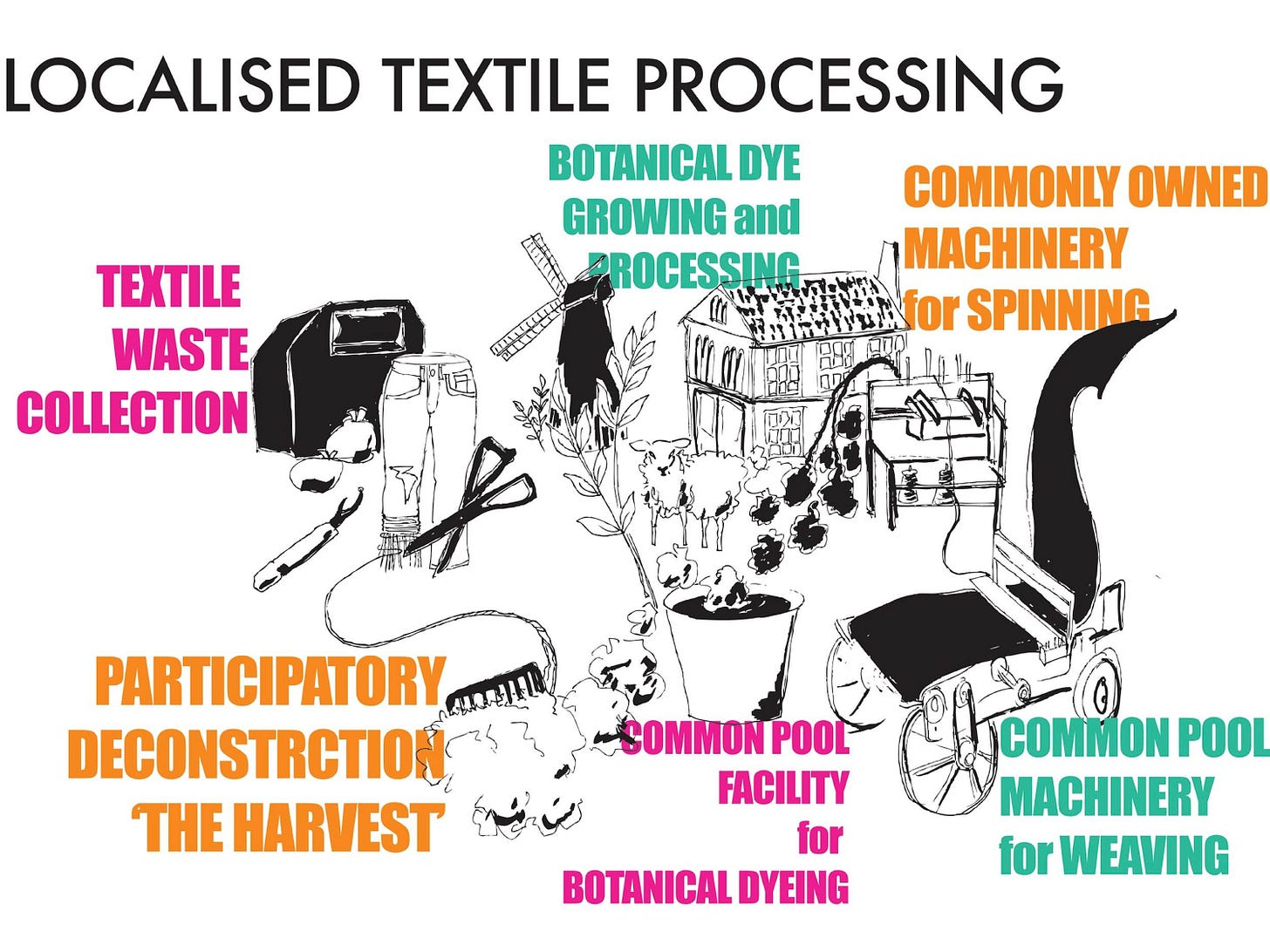

Joel and are are keen members of a small subgroup of commons researchers and thinkers who focus on reimagining clothing systems. Joel and I look at participatory clothes making and urban immersive learning, alongside Zoe Gilbertson researching Regenerative flax, Nick Evans looking at mid scale fibre machinery, Allan Brown and Sharon Kallis exploring lowfi homegrown, Sandra Neissen sharing her research into indigenous clothing systems and their vulnerability to colonialism, and many more teachers, lecturers and researchers, usually with a love of clothes, looking for a hopeful way to make them

.

What's fascinating, for us, about making clothes, is that it used to be an absolutely central activity of civilization. Spinning (fibre into yarn) in particular, would have likely been a daily meditation before mechanisation, as it is the most time consuming part of textile production. bearing this time consumption in mind, it is astonishing, the creativity, complexity and frivolity of preindustrial 'fashion', particularly peasant fashion (which was made by the wearers more or less). The intensity of preindustrial clothes making suggests that (at certain points) people in pre industrial cultures had quite a lot of free time. Free time to dye pretty colours, and weave extra cloth for big puffy sleeves, and big underskirts, and overskirts, and embroider everything. Nothing on the the same level as contemporary global north wardrobes, but on the flip side there wasn’t a clothing dump in the Atacama desert either.

We’ve already conducted a thought experiment as to the ‘necessity’ clothing, but clothes have also, it would seem, always been more than that to humans, they are perhaps our most immediate form of artistic expression, (along with hairstyles and singing...?) In modern times, vast majority of people express themselves as smart casual office workers, or hiking bros, or something similarly on the navy blue to khaki scale of invisibility, and act as if this is a non-expression, which might be described as a post enclosures ‘cope’. Clothes are kind of fascinating, because they always mean something beyond just warmth and dryness and protection from sunburn. They are a form of communication between us, and they can bring us a lot of joy when we get the colour and the cut and the fabric that we’re dreaming of. They show us how humans aren’t just trying to survive, but are drawn to creativity and aesthetic expression as part of their thriving. Care Home Farm holds this theory of humans at its core, it seeks to make space for the fullness of this aesthetic/function combination, and the drive of humans to create, iterate, evolve and reimagine in their day to day existence.

Mapping clothing production onto an inter sufficient community, could be seen as making life unnecessarily hard for yourselves. Mass production kicked off with clothes production, and I’ve written and spoken A LOT about how we’re now living in that fairy tale with the magic porridge pot stuck on; about to drown in nylon yoga leggings. There are many voices in the sustainable fashion world, suggesting that we should just stop making clothes altogether for a couple of hundred years, and wear the ones we already have, and I wonder how many people coming out of global north culture, will see this as the best option, saving ourselves a whole heap of hassle, whilst we learn to grow wheat without fertiliser again.

However, for Joel and I- who love making clothes and dislike wearing mass produced normcore, living on an inter-sufficient farm is partly so that we can make clothes again. Lol.

We’ve tried making good clothes other ways- sustainable businesses and such, and our findings are, that if you want to live in a way where your productivity produces CARE (care for the landscape, care for your body, care for the bodies of those around you, care for future generations etc), then you have to be entirely outside of a rent based, debt based economic system. So for us the question isn’t- Why would we bother making our own clothes? It’s more- Why would we bother creating a whole new system for community living if we don’t get to make our own, absolutely brilliant, clothes? It seems likely to us that other members of our future village will have the same feelings about different things; ideally those things could be lip balm, plum eau de vie, salami, leather chairs, handblown glass ware, willow backpacks and natural swimming ponds…

Some secondhand clothing and secondhand textiles will certainly be very useful, but I wonder how much unwanted clothing will be useful in an inter-sufficient community of land based work. In my experience, current clothing trends are either suited for being mostly indoors, or are heavily reliant on plastic. Synthetic clothing releases micro plastics during washing, wearing and disposal, so it's not suitable for a completely circular system, I also personally find them really gross. If you are a seasoned natural fibre shopper, like myself, you’ll know that it's hard to find well made natural fibre clothing secondhand, and it's often not very cheap, which negates the convenience element. (a natural dyer told me that synthetic dyes probably release micro plastics so any commercial dyed natural fibres are still tainted, waaaaahhhh)

There’s something about shared aesthetics that are powerful. About visible differentiation. About clothing that carries the symbolism of its process (which our clothing undoubtedly does, in a bad way). Clothing made entirely from native british natural fibres, on fossil fuel free farmscale machinery, or by hand, that is cut bespoke to the body and taste of the wearer (and is made with the embedded skill of people who have been sewing for 20 years plus) will subvert usual symbols of wealth and status in ways that are hard to fully imagine. Playing with this symbolism, co-creating new aspirational aesthetics, expressing heartfelt care through objects that are currently part of the subtle webs of oppression that keep us all separated, this is some of the intellectual and spiritual work of Care Home Farn that feels exciting to Joel and I. It requires whole new systems of work organisation, and humanscale tech, even designing this new tech feels exciting to Joel and I- humans need to remember that we build machinery, we can build different machinery, we can hack machines that we already have to run on pedal power rather than electricity.

The production of clothing gives us some important insight into work and well being. Pre-industry, spinning wasn’t very recognisable as work. The drop spindle is portable, goes with you, like knitting on the train, you can spin in groups whilst you all chat. You can spin with your baby crawling around nearby, you can spin at home in the evening by the fire. Industrial spinning is too loud to be heard over, it takes place in a designated factory where someone sees you clock in and clock out, it requires many less people to just one massive machine, and of course- it makes profit for the machine owner rather than clothes for the mill worker. Not to mention the fossil fuel power sources.

Research into handcrafts shows us that they are part of our mental health coevolution. We reach theta states, or flow states when we engage in repetitive skill motions, similarly to when we meditate or pray. I am almost certain that there will be a place for both midscale tech and pure handmaking on the Care Home Farm. The flexibility and simplicity of hand tools make them more tolerant of regenerative fibre production, more flexible for work that fits in with care, and more creative for meeting aesthetic needs. But on the other hand, I do like the comfort of knitted jerseys, so a machine for fine spinning and a circular knitting machine tracksuiting would be fun.

In the last post we discussed food production within regenerative forest gardening systems. Fibre production can go alongside food in these systems- Silk moths live on Mulberry which is a perennial tree crop (successfully grown in this country for hundreds of years despite the propaganda about red mulberry). The Dye plant Madder is a perennial that can be included in an understory, whilst weld and woad/indigo self seed easily or can be included in market gardens. In Between your tree rows you can graze fibre animals like heritage sheep, angora goats, cashmere goats, or angora rabbits (which we are currently trialling in London :-)) Annuals like flax should probably go in a crop rotation with something like peas for animal feed, whilst hemp (which is being trialled at Wakelyns in Suffolk) is rumoured to improve soil fertility.

Producing our own clothes is also a bit about taking responsibility for our lifestyles. In Kate Sopers work on Alternative Hedonism, she advocates for humans interrogating what brings them joy. Understanding the ‘costs’ or ‘means’ required to produce our joy is part of that interrogation. We rely to readily on vulnerable workforces in the global south, rather than granting them equal agency to explore their own joy. If we are making in house, then we have the full spectrum of experience to make negotiations over how many pairs of jeans per person meaningful and experiential. Given how absolutely fun it is to make clothes that you wear, and wear clothes that you make, I expect this equation to come out better than what people might think. And I expect that to be the same for every beautiful handcrafted item we create and use at Care Home Farm. But either way, it will be real, and that’s relaxing

.

I am very lucky to work with someone who can think through and communicate our shared understanding with such clarity, generosity and humour - and literally make me look so good!